In January, Z got an Individualized Education Program – a legal document specifying the special education services he’s entitled to. He is covered by federal law!! Go America! Go taxpayer dollars at work! Z needs help learning to write, because his handwriting is indecipherable even to adults trained in deciphering children’s handwriting, and he is slow to form sentences and translate his abundant and fantastical imagination and wealth of knowledge, real or fictitious, to the page.

It turns out you learn a lot about your kid when you go through the special education process. They (specialists, I really have no idea who they are) give your kid a bunch of tests (I really don’t know about what) and then they come up with a bunch of evaluations and conclude that your child fits into one of 13 state-mandated categories that necessitates extra help in school. Which, by the way, every kid should get.

Through this important process, you learn things like: your child has a “slow response time” when answering questions, can copy shapes onto a piece of paper, slides words across a page as he reads (whatever that means), recognizes sight words comparable to other kids in his age cohort, has above average verbal reasoning skills (wonder where he got that from), can hold the pencil with a quadropod grasp but can not stabilize his forearm and shoulder muscles while writing, is in the 16th percentile for forming his lowercase letters, and has difficulty shifting his ocular focus from one stationary object to another. Good to know. Also, he can identify that sweet and sour are both “tastes,” and he calls the nose and ear “structures on your body.” The latter got him only partial credit on the cognitive reasoning test.

Wait, what? Personally, I think it should win him the Kid’s Award for Poet Laureate.

Through this process, we also learned – I mean we already knew, but now it is clinically confirmed – that Z is distractible, slow to follow directions, slow to process information and needs multiple reminders to follow classroom routines.

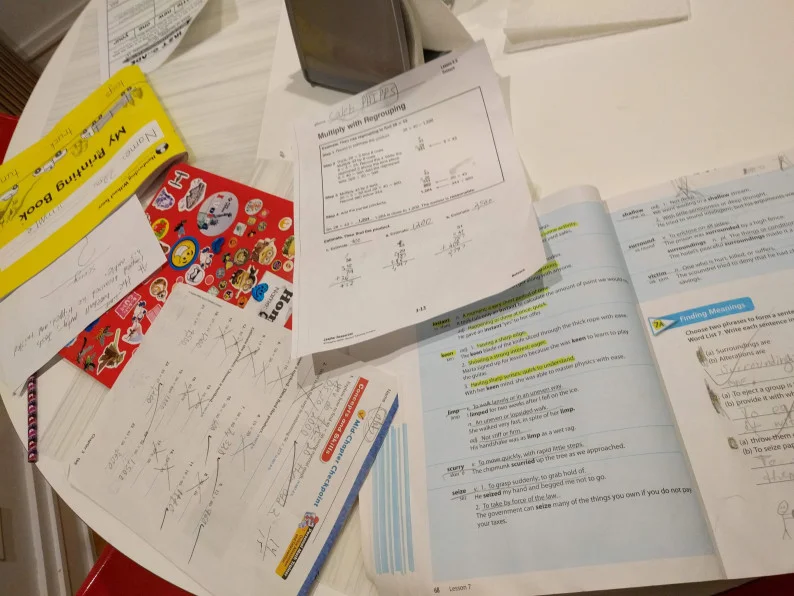

His desk is a mess, he’s the last kid to take his coat off in the morning and the first kid to lose his water bottle before lunchtime.

I used to think that one day Z would just wake up and realize that he had to get to school and put his coat on and get out the door like everyone else in the world. But now I’m starting to think that this will never happen.

Because of this: one day recently, one day when we need to fetch C at an appointed time from an appointed place, or they’ll start charging me more for whatever activity I already pay too much for, I’m reminding Z, then begging Z, to get ready to go.

Can you get your socks on? I ask Z. We need to pick up your brother. And we’re running late.

Please. Get. Your. Socks. On. I plead.

Please please, please, please, please, please put the socks on.

I hand him his socks. This will work.

He doesn’t even look at them. He is sitting on the bench, the bench T bought for the specific purpose of putting on socks and shoes, and he is holding the socks in his hand and he is not even looking at them or budging, or aware maybe that I have given him something that he is clutching in his hands.

It’s time to go, I say.

I don’t even think he knows that we’re going somewhere.

“Mom,” he finally says. “When the sun explodes, am I going to be alive?”

I don’t know, I say. But you will definitely not have your socks on.